Reflections on Lent

Augustine: "Lent is the epitome of our whole life"

I recently finished John Marco Allegro’s The Sacred Mushroom and the Cross, which tells a fascinating story of First-Century hippies in the Near East tripping balls on mushrooms and developing the moral and ritual infrastructure of the Early Church. Unsurprisingly, Allegro’s thesis is highly controversial and is considered heretical by virtually all Christian institutions (save those actually adorned with psychedelic mushrooms in parts of Brooklyn and San Francisco). While Allegro was at times uncomfortable, he was always intriguing, and I was amazed by his command of historical and archaeological evidence, some of which does appear to corroborate a few of his claims. Inundated both with his unorthodoxies and recency bias, I am today persuaded that psilocybin use (or maybe abuse) definitely played some role, if even a small one, in Early Church identity-formation.

And Allegro’s framework remains relevant. Next week, on Ash Wednesday, the 2025 40-day Lenten fast initiates, and several billion Christians will undertake a seasonal ritual to which Allegro ascribes a psychedelic origin. Flavored by Allegro, my goal here is to provide a deeper meditation than my standard Lenten promise: “I will not eat chocolate for 40 days.”

If there is a thesis for these reflections, it is this: the purpose of Lent is to prepare the Christian soul for Easter through a structured period of fasting, prayer, and almsgiving. The practice evolved from ancient mystic ritual and ascetic tradition — drawing on scriptural mandates and historical custom — and was later refined and codified by scholastic theologians; in essence, it is the annual season of thoughtful preparation for Heaven.

I. Lent as a Mystical and Purificatory Rite

Allegro’s wild hypothesis casts Lent in a new light — as a mystical rite with possible psychedelic roots. While I flatly reject Allegro’s claim that “Christ” was just a codeword for psilocybin mushrooms, even mainstream scholars acknowledge that early Christian environs were awash in ecstatic religious traditions. In the ancient Near East, mystery cults routinely mixed drugs with religious ritual to induce transcendent experience. It is reasonable to accept that early Christian fasting and worship borrowed some of this entheogenic ethos, aiming to open the soul to divine encounter.

At the very least, even without literal mushrooms, the early Church saw Lent as a time to seek mystical union with God through bodily discipline. Fasting (with or without psychedelics) was a portal to the sacred — a controlled deprivation of the senses to heighten spiritual sensitivity. The Lenten fast, therefore, can be understood as a feature of this broader mystical impulse: a quest to purge the ordinary and touch the extraordinary.

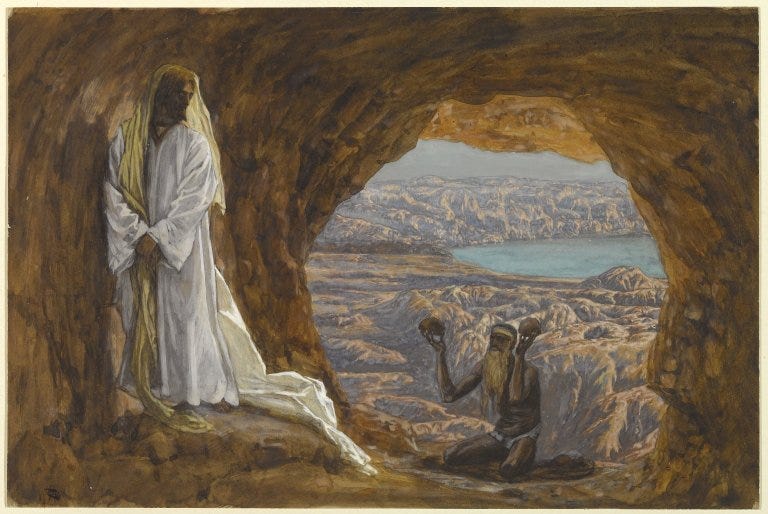

Crucially, the practice of fasting as a preparation for divine encounter is rooted deeply in biblical precedent. The heroes of Scripture themselves undertook lengthy fasts that seem almost otherworldly. Moses ascended Mount Sinai and remained with God “forty days and forty nights, without eating bread or drinking water,” during which he received the covenant Law (Exodus 34:28). Likewise, Jesus retreated into the wilderness and fasted for forty days before launching his public ministry, a period of intense temptation and spiritual fortification (Matthew 4:1–11).

The patristic tradition thus understood these forty-day fasts as a roadmap for spiritual growth. St. Augustine points out: “Moses and Elias and our Lord Himself fasted for forty days,” the Law, the Prophets, and the Gospel — to teach us “not to cling to this present world” but to be purified for divine things. In short: the 40-day span of Lent deliberately mimics the sacred fasts of Moses and Christ as a path to encounter God. Fasting empties the body, allowing the soul to be filled with the Word.

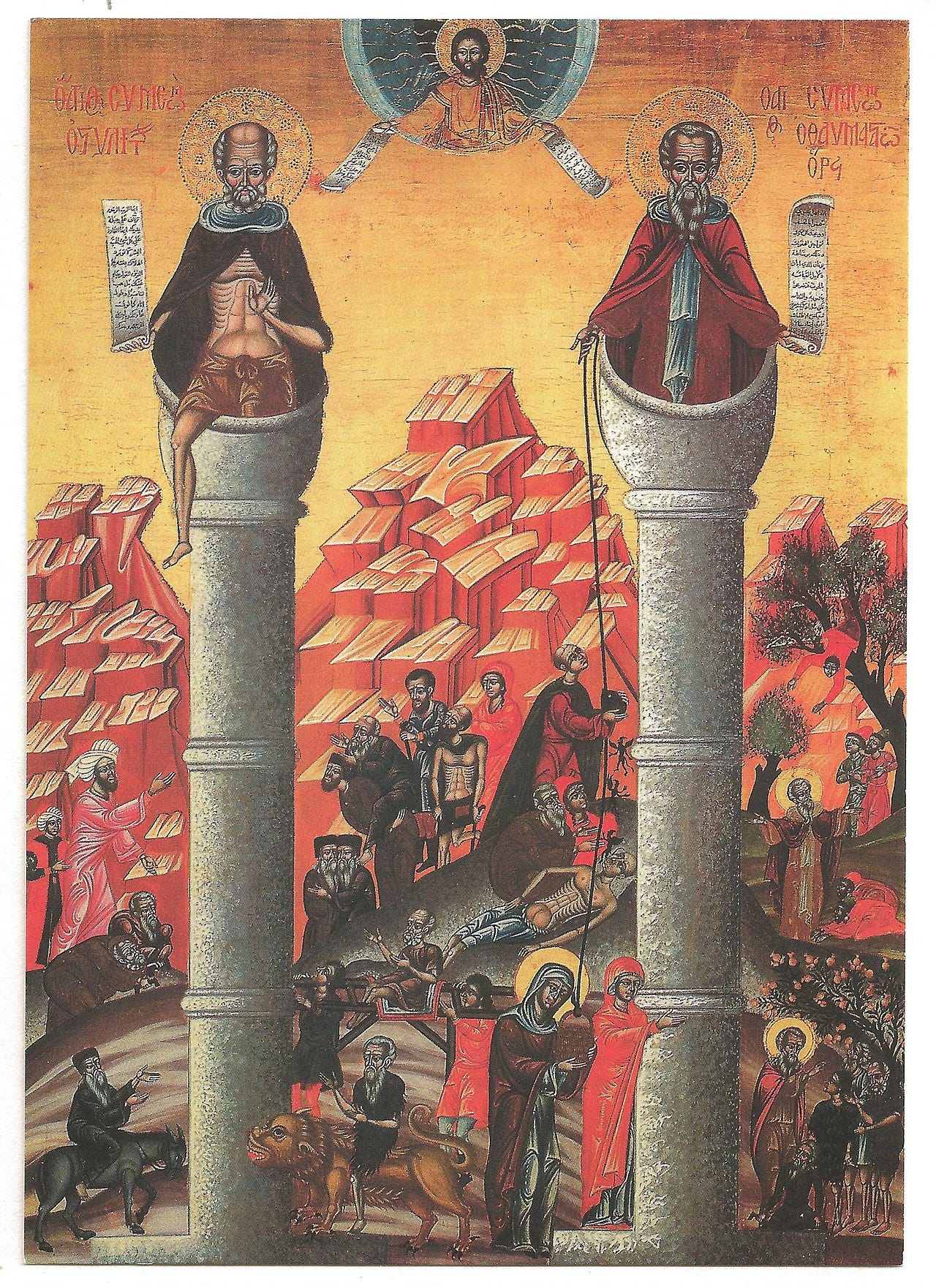

This framework was embraced and radicalized by the earliest Christian ascetics. In the 3rd and 4th centuries, the “Desert Fathers” fled to the wilderness to seek God beyond the noise of society. Figures like St. Anthony of Egypt lived on minimal bread and water, praying for hours each day. Even more extreme were the Syrian monks, who turned asceticism into an art.

Anthony of the Desert and his fellow hermits...practiced vegetarianism, extreme fasting and mortification of the flesh. In Syria, the desert monks were even more extreme. St. Simeon Stylites...fasted for a year...and finally took residence on a platform atop a pillar...where he lived for 37 years

These staggering feats of self-denial, while perhaps fanatic, were motivated by “purity of heart” and pursuit of spiritual symbiosis with the divine. The desert ascetics believed the body must suffer to free the mind, turning it to God’s vision. By subduing all physical comfort — even to grotesque extremes — these Saints sought to induce unclouded spiritual clarity. Lent, in its more ordinary form, carries forward this mystical-ascetic tradition: it invites Christians everywhere to join (at least for a season) the desert quest of freeing the soul from fleshly distractions.

Medieval theology later distilled these insights on fasting into canonical principles. St. Thomas Aquinas, drawing on the Church Fathers, taught that fasting: “is practiced for a threefold purpose. First, in order to bridle the lusts of the flesh…[and] lust is cooled by abstinence…Secondly…that the mind may arise more freely to the contemplation of heavenly things…Thirdly, in order to satisfy for sins.” To Aquinas, fasting becomes a kind of therapy for the soul: suppressing unruly bodily passions and elevating the rational mind. Augustine, too, extolled fasting in precisely this purificatory sense:

Fasting cleanses the soul, raises the mind, subjects one’s flesh to the spirit…scatters the clouds of concupiscence, quenches the fire of lust, [and] kindles the true light of chastity.

For both Augustine and Aquinas, Lent’s ascetic rigors are ordered to inner transformation. The Christian ethos aims to heal the soul, supplanting the dominance of base desires and invigorating a singular desire for God. Lent derives from a mystical purification ritual — one that may have ancient, even psychedelic echoes — but that ultimately hinges on the very down-to-earth practice of fasting to “crucify [the] flesh with its passions and desires” (Galatians 5:24). Through the crucible of self-denial, the soul is readied to encounter the holy.

II. Lent as a Season of Penance and Corporate Renewal

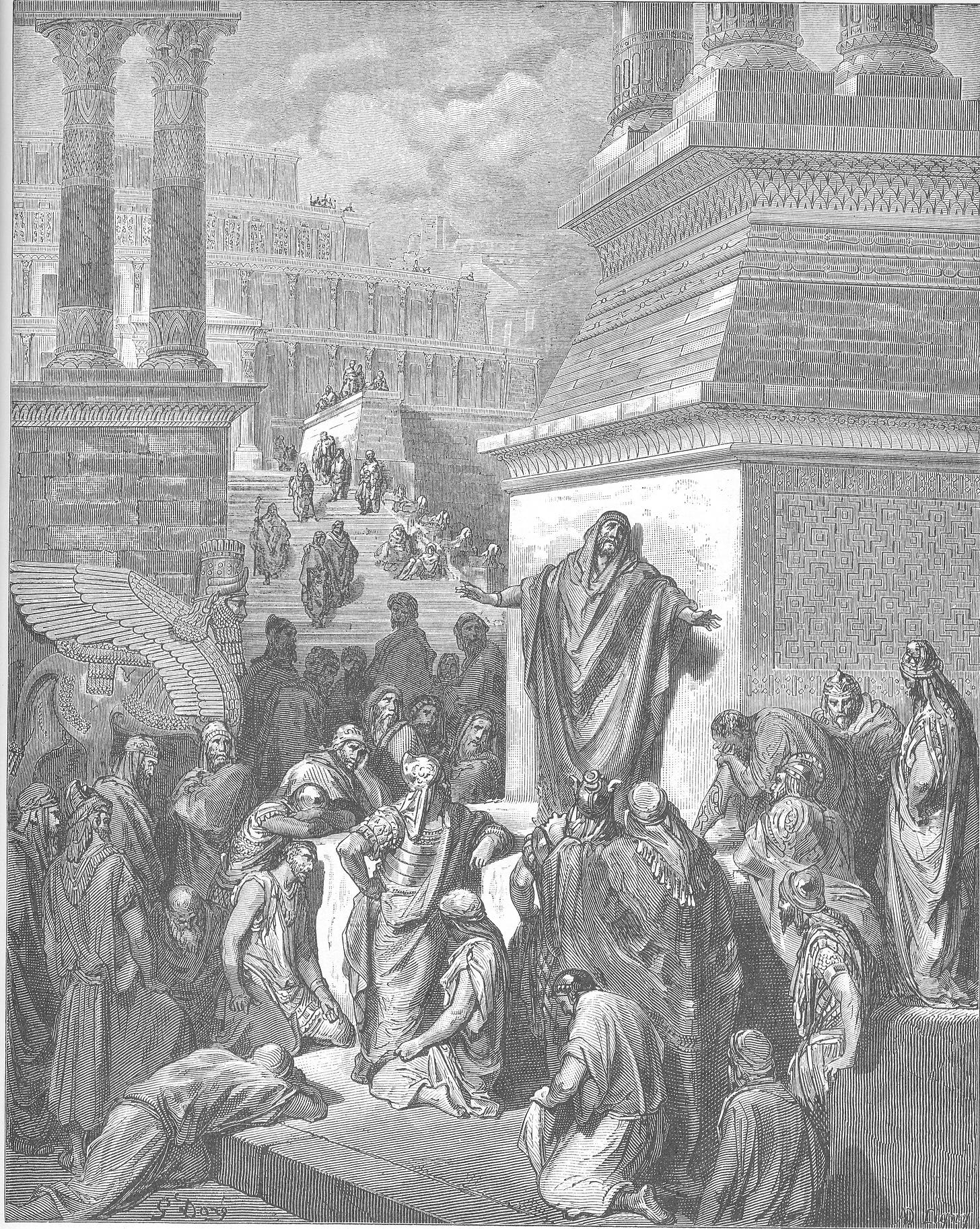

If Lent’s roots reach into mysticism, its daily implementation has always emphasized penitence. The penitential character of the Lenten fast is evident from Scripture onward: fasting is a natural language of repentance. The city of Nineveh provides perhaps the best dramatic example. After the prophet Jonah’s warning of doom, “the Ninevites believed God. A fast was proclaimed, and all of them, from the greatest to the least, put on sackcloth” (Jonah 3:5-10). Seeing their sincere repentance, God spared the city. Likewise, the prophet Joel, amid a national crisis, relays God’s plea: “Return to Me with all your heart, with fasting, with weeping, and with mourning. Rend your heart and not your garments.” Fasting, in these precedents, is a tool of collective contrition — an outward act that expresses inner sorrow and conversion (Joel 2:12–13). Lent squarely inherits this biblical ethos: it is 40 days of sackcloth for the soul, a time to acknowledge our sins and spiritually “reset” our lives.

Jesus himself reinforced fasting as a form of personal penance, provided it is done sincerely. In the Sermon on the Mount, Christ assumes his disciples will fast, but he sharply warns against doing it for show: “When you fast, do not look somber as the hypocrites do…But when you fast, anoint your head and wash your face, so that your fasting may not be seen by others but by your Father who is in secret.” (Matthew 6:16-18). The Lord’s teaching makes clear that fasting is not about public piety or earning human admiration; it is about authentic repentance before God.

This gospel principle would shape the developing practice of Lent: the emphasis shifted from extreme ascetic feats to interior conversion. Fasting, prayer, and charity in Lent are to be done “in secret,” with a contrite heart, not a prideful spirit. Yet even as Christ spiritualized fasting, he did not abolish it — implying that some external form of repentance (like fasting) remains necessary. Thus the Church continued to prescribe communal fasting as a tangible framework in which the faithful could collectively repent each year.

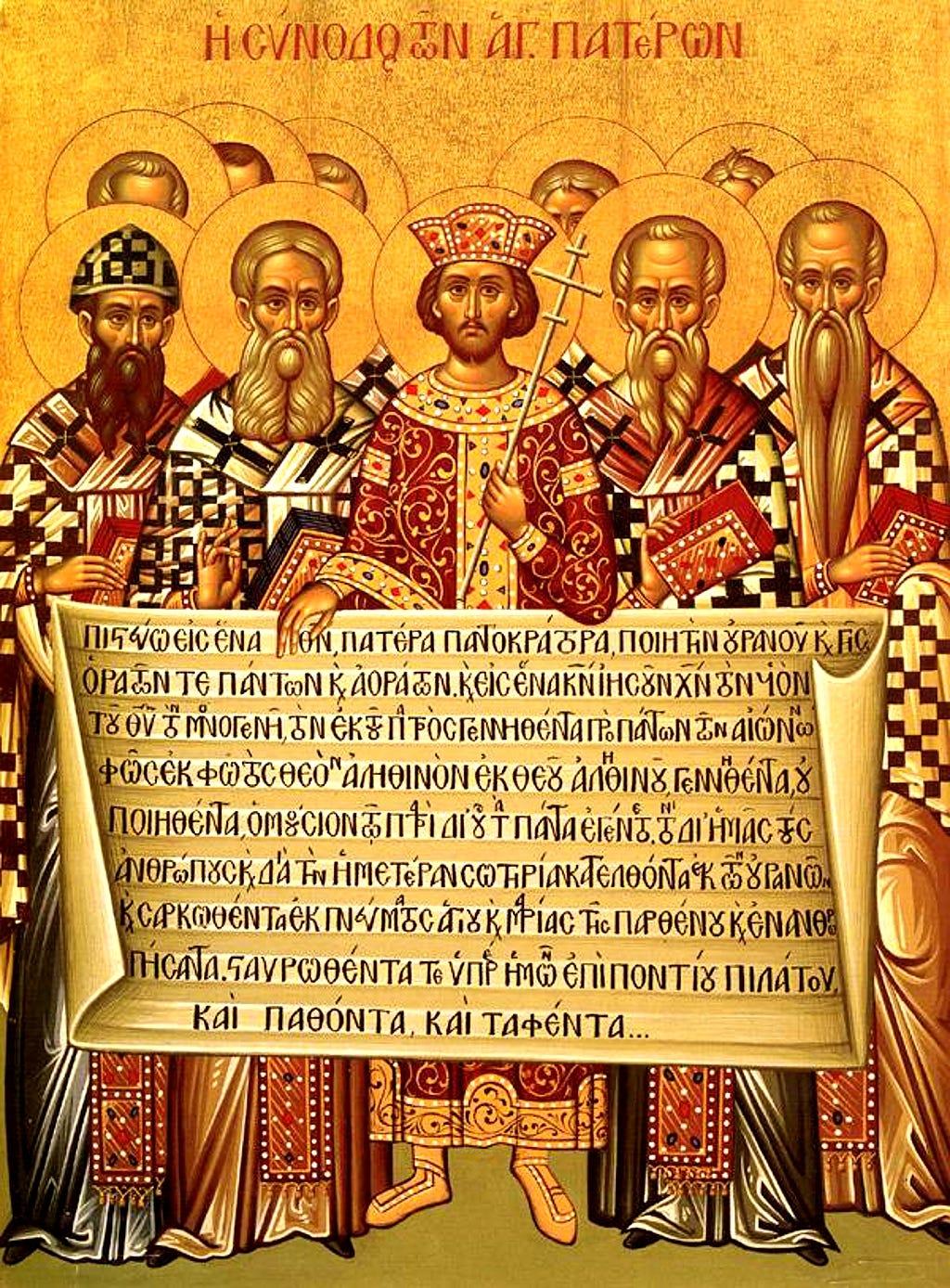

By the early centuries of Christianity, the Church began formalizing this annual season of penance. Various local traditions of pre-Easter fasting coalesced into what we now call Lent (from Quadragesima, “Fortieth” day). The pivotal moment of standardization came with the Council of Nicaea (AD 325), which for the first time mentions a 40-day Lent as a period of fasting in preparation for Easter. While practices still varied regionally, Nicaea’s endorsement gave Lent a universal legitimacy.

Within a generation, St. Athanasius — the bishop of Alexandria — could testify that a forty-day fast before Easter was observed “by all the world.” In 339, Athanasius wrote a Paschal letter urging his flock to keep the Lenten fast, “to the end that while all the world is fasting, we who are in Egypt should not become a laughing-stock as the only people who do not fast.” And, by the mid-4th century, Lent had become a normative institution across Christendom: an expected, corporate exercise of penance. No longer was fasting the province of monastic virtuosi alone; it was the shared duty of the entire Christian people. The Church recognized that everyone needs a season of penitence — a yearly spring-cleaning of the soul — lest complacency or sin accumulate unchecked.

Saint Augustine, who preached frequently on Lent, understood it as a time of collective humility. He exhorted his congregation at the start of Lent with an almost military seriousness: “an appropriately solemn sermon is your due so that the word of God…may sustain you in spirit while you fast in body.” Augustine sees the whole Church as entering a kind of spiritual boot camp each Lent — fasting in body so that the community may be renewed in spirit. He describes how Lent is meant to “crucify” our pride and fleshly desires, uniting us to Christ’s Passion. Importantly, this penitential journey is not undertaken alone but as a body. Augustine elsewhere beautifully calls Lent “the epitome of our whole life,” urging Christians to live year-round in the spirit of Lent but to redouble their efforts in these forty days.

Lent condenses and intensifies the ongoing work of repentance that defines Christian life. For a brief season, the entire Church walks in step through the desert of penance, sharing the burdens of fasting, prayer, and almsgiving as one people. Lent’s communal nature checks against the individualistic pride that could come from private asceticism; we all humble ourselves together, as fellow sinners in need of mercy. By the time we arrive at Easter, having “afflicted our souls” (Lev 16:29) for a time, we are ready as a community to rejoice with cleansed hearts. The genius of Lent as a penitential season is that it harnesses the wisdom of routine: year after year, it realigns us with the life of conversion.

III. Lent as an Imitation of Christ and a Participation in the Paschal Mystery

Lent ultimately derives its deepest purpose from imitation of Christ. Forty days are explicitly modeled on Christ’s own 40-day fast and on His suffering and journey to the cross. The Christian who keeps Lent is consciously walking in Christ’s footsteps, enacting in miniature drama of Jesus’s self-denial, Passion, and resurrection victory. In the words of St. Paul, believers are called to “have this mind among yourselves, which is yours in Christ Jesus” — the mindset of humility and obedience — for Christ “humbled Himself and became obedient unto death, even death on a cross.” (Philippians 2:8). During Lent, Christians seek to adopt that kenosis: emptying themselves of attachments and ego, taking up the cross of discipline, and following Jesus into the desert of trial.

Historically, Lent also became a time when new Christians would most literally imitate Christ’s journey through the sacrament of Baptism. In the early Church, catechumens spent Lent in intense preparation and fasting before baptism at the Easter Vigil. This practice highlighted the paschal mystery dimension of Lent: it is about dying and rising with Christ. In Baptism, a person sacramentally dies with Christ and is reborn to new life (cf. Romans 6:3-4). So, during Lent, not only catechumens but all the faithful enter into a kind of spiritual death — dying to sin, crucifying the “old man” — in order to renew their baptismal identity at Easter.

The Paschal Mystery refers to Christ’s Passion, Death, and Resurrection; Lent is ordered by that mystery. We fast and embrace the cross now (a type of death to self), in confidence that this will lead to the joy of resurrection — both at Easter and ultimately in God’s kingdom. St. Paul captures this dynamic in a trustworthy saying: “If we have died with Him, we shall also live with Him; if we endure, we shall also reign with Him” (2 Timothy 2:11–12). The small “deaths” we die in Lent by self-denial are a participation in Jesus’s own death, and thereby they become a path to share in His life. Thus Lent has a profound eschatological thrust: it trains our eyes on the life of the world to come, teaching us that the road to eternal Easter necessarily passes through the cross of sacrifice.

The concept of a special fast before a springtime festival of renewal is not unique to Christianity. The ancient Romans held February as a month of purification (named after the Februa rites) to cleanse the city before the new growth of spring. Similarly, in the Near Eastern cult of Cybele, devotees mourned the death of Attis each year with fasting and lament before celebrating his (mythic) resurrection — a ceremony not unlike a pagan Lent. And of course, Judaism’s Yom Kippur is a powerful and direct antecedent: an annual day of atonement marked by total fasting, prayer, and confession of sins to renew the covenant with God.

Christianity, far from abolishing such rhythms, baptized them into the service of Christ. Lent became the Church’s great annual fast, directing the ancient human impulse for purification toward union with the Paschal mystery. As Pope St. Leo the Great taught in the 5th century, the forty days are observed “that the affections of the mind may become purer” and that the faithful may fulfill “the apostolic institution of the forty days” of penance. In other words, by fasting for forty days in imitation of Christ, Christians throughout the ages seek not only personal purification but a closer identification with Christ crucified and risen.

Saint Thomas Aquinas articulates the spiritual logic of Lent’s triad — fasting, prayer, and almsgiving — as an integrated method of conforming one’s soul to Christ. Fasting disciplines the flesh and fosters chastity (echoing Christ’s purity); prayer, which is intensified by Lent, “allows the mind to arise freely to the contemplation of heavenly things,” echoing Christ’s constant communion with the Father; and almsgiving, or charity, is the practical exercise of “love of neighbor,” by which we imitate Christ’s love and make reparation for sins.

Aquinas notes that the fruits of fasting should be used to feed the poor — thus uniting self-denial with charity. In this way, the Lenten disciplines align the Christian soul with the core aspects of Jesus’s life and teaching: self-denial, prayerful obedience, and sacrificial love. The goal is not suffering for its own sake, but a purification of heart that makes room for divine love. Through prayer, we seek to love God more; through almsgiving, to love our neighbor; through fasting, to remove impediments to both.

These practices prepare the soul much like an athlete training for a contest — and the “contest” is the solemn commemoration of Christ’s death and the joyous celebration of His Resurrection. To use some flowery language: Lent tunes the Christian heart to the key of the Paschal Mystery, so that when Easter dawns, we may sing Alleluia in harmony.

Conclusion

Lent is preparation for Easter, yes — but on a deeper level, it is preparation to encounter God, both now and at the end of our lives. Forty days of structured fasting, prayer, and almsgiving, offers a seasonal period of intentional formation. We go into the “desert” with Jesus so that, come Easter, we might emerge transformed.

The brilliance of Lent is that it evolved from ancient mystic ritual and ascetic tradition — as Allegro’s wild thesis reminds us — but was then refined by scripture and theology. Lent echoes basic human religious instincts (purification, repentance, imitation) but is firmly anchored in Christ’s story. Augustine preached that we must live all our life as a kind of Lent. In his words: “we have to do so all our lives, we must make an even greater effort during these days of Lent…Lent is the epitome of our whole life.”

Christians embrace these forty days as a microcosm of the Christian journey: a journey from ashes to Easter, from death to new life. And that ethos, ultimately, is the purpose of Lent — to lead us, with purified hearts, to the empty tomb and beyond, into the fullness of life in the Risen Christ.