Myth and Memory

Examining the Literary and Archaeological Roots of the Capitoline Triad and the Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus

Part I: Literary Roots

Having stood for roughly half a century at the time of Livy’s Ab urbe condita (27 to 9 BC) and Virgil’s Aeneid (29 to 19 BC), the Aedes Iuppiter Optimus Maximus Capitolinus (IOM) was a ubiquitous symbol of Roman power and religious life by the first century BC. IOM’s central location atop the Capitoline’s west summit — overlooking the Forum and proximate to the curia, the seat of Republican power — as well as its practical religious function for auspicatus ensured that the temple occupied a central position in late Republican literature. As Virgil and Livy craft mythical histories of Rome’s progenitors in their respective works, IOM emerges as a central feature of Roman identity formation. By deploying myth, and perhaps some blurry cultural memory rooted in fact, late Republican literature offers narrative explanations for the location, foundation, deities and practices of IOM.

Virgil endeavors to entangle IOM with Rome’s legendary progenitor, Aeneas, highlighting the unparalleled holiness of the temple and its connection to worship of Jupiter. Jupiter immediately emerges as central in Virgil’s corpus. In Book I, Jupiter’s prophecy to Venus sets Aeneas’ voyage in motion. More directly, the Capitoline appears twice in the Aeneid. First, in Book VI, Anchises speaks to Aeneas: “Mummius, triumphant over Corinth, shall drive a victor’s chariot to the lofty Capitol … he will avenge his Trojan sires and Minerva’s polluted shrine” (6.836). Virgil thus connects Aeneas to the triumph, the Capitoline (the triumph’s terminus), and Minerva, a goddess of the Capitoline triad worshiped at IOM. Second, in a longer passage and more direct reference to IOM in Book VIII, Virgil depicts Evander guiding Aeneas through the future site of Rome: “From this they climbed the steep Tarpeian hill, the Capitol, all gold to-day, but then a tangled wild of thorny woodland. Even then the place woke in the rustics a religious awe, and bade them fear and tremble at the view of that dread rock and grove. ‘This leafy wood, which crowns the hill-top, is the favored seat of some great god’” (8.347-352). Virgil’s mention of “gold” likely refers to the gilded IOM of his day. More importantly, Virgil once again connects Aeneas and Rome’s mythical Trojan heritage to the sacred ground of the Capitoline. Again in Book VIII, Virgil explicitly connects the Capitoline to Jupiter: “The Arcadians say Jupiter’s dread right hand here visibly appears to shake his aegis in the darkening storm, the clouds compelling” (8.352-354).

Livy picks up where Virgil left off, emphasizing two pre-Roman Jupiter cults that anticipate IOM. Livy succinctly summarizes the tale of Aeneas and proceeds to his death, noting that Aeneas is posthumously deified as “the indigenous Jupiter”: “His tomb … is situated on the bank of the Numicius. He is addressed as ‘Jupiter Indiges’” (1.2). In this way, Jupiter-worship is infused into the essence of Rome’s heritage through its first hero. Aeneas’ son, Ascanius — perhaps Rome’s second hero — then migrates from the Trojans landing spot at Lavinium to the “foot of the Alban Hills,” where he founds Alba Longa (1.3). The Albans similarly anticipate Jupiter worship on the Capitoline with their worship of Jupiter Latiaris (Jupiter of the Latins) at a sanctuary atop their own sacred hill, Mons Alba.

Livy’s first mention of the Capitoline also occurs in the context of Jupiter worship, focuses on Rome’s direct progenitor and eponym, King Romulus (r. 753-716), and entangles Jupiter worship, the Capitoline, and military success. After slaying the King of Caenina in one-on-one combat, Romulus dedicates the spolia opima to Jupiter atop the Capitoline. Livy writes, “he mounted to the Capitol with the spoils of his dead foe … He hung them there on an oak … marked out the site for the temple of Jupiter, and addressing the god by a new title, uttered the following invocation: ‘Jupiter Feretrius! … I, Romulus a king and conqueror, bring to thee … Such was the origin of the first temple dedicated in Rome” (1.10). Livy notes that the temple to Jupiter Feretrius was later expanded in the wake of the military successes of Ancus Martius (r. 640-616 BC), reinforcing the connection of a Capitoline Jupiter to Rome’s military success (1.33).

Jupiter worship atop the Capitoline is embedded into Rome’s history by virtue of Romulus, the nation’s first monarch and perhaps greatest legendary hero. Rome’s connection to Jupiter is reinforced during the Sabine War, when Romulus attributes the city’s foundation to Jupiter and invokes the title “Jupiter Optimus Maximus” for the first time. Livy writes, “‘Jupiter, it was thy omen that I obeyed when I laid here on the Palatine the earliest foundations of the City … Jupiter Optimus Maximus bids you stand and renew the battle’” (1.12). Indeed, Romulus himself was apotheosized in the Campus Martius, just beyond the Capitoline, in a strange manner that appears to invoke Jupiter. Livy explains, “A violent thunderstorm suddenly arose and enveloped the king in so dense a cloud that he was quite invisible … he had been snatched away to heaven by a whirlwind … ‘a god, the son of a god, the King and Father of the City’” (1.16).

Virgil and Livy thus connect Rome’s legendary leading men to hilltop Jupiter worship, signifying that Jupiter is indeed “the best and greatest,” as IOM’s name suggests. Virgil’s Aeneas is party to Jupiter’s prophecy and feels the power of Jupiter upon his visit to the Capitoline. Livy’s Aeneas becomes Jupiter after his death. Ascanius, the second great man of Roman legend, establishes a Latin town famed for its Jupiter sanctuary. Indeed, throughout Ab urbe condita, Livy often turns to Mons Alba for signs from Jupiter, including storms of stones, among other omens. Peak sanctuaries to Jupiter are therefore emphasized by Livy, underscoring the cultural importance of IOM. Finally, Romulus, with the temple to Jupiter Feretrius, initiates the tradition of Jupiter worship on the Capitoline and, during his apotheosis, appears to be plucked up into the sky by Jupiter himself.

A mystery still remains regarding the two goddesses of the Capitoline Triad, Juno and Minerva. However, beyond the obvious idea of a divine royal family — king (Jupiter), queen (Juno), and princess (Minerva) — both Virgil and Livy provide clues as to Juno’s and Minerva’s significance.

Juno worship occupies a place of significance to both Virgil and Livy. From the very beginning of the Aeneid, Virgil emphasizes Juno’s power, establishing her as the Trojan’s primary antagonist. Virgil also makes a point to highlight Dido’s temple to Juno in thriving Carthage, emphasizing the importance of Juno worship for a successful city (1.446). Livy further reinforces themes of Juno’s power and the importance of reverence to Juno. When Romans capture Veii, for example, Livy highlights reverence to Juno with a votum and invitation for Juno to relocate to Rome: “Queen Juno, who now dwellest in Veii, I beseech, that thou wouldst follow us, after our victory, to the City which is ours and which will soon be shine, where a temple worthy of thy majesty will receive thee” (5.29). Finally, Livy mentions the vowing of a temple to Juno Moneta flanking IOM on the Capitoline’s east summit, the Arx (7.28).

Minerva’s centrality is also hinted at by Virgil. As aforementioned, Virgil mentions Mummius’ vengeance as a consequence of his reclamation of Minerva from the Greeks’ “polluted shrine.” Similarly, among the limited possessions he takes from Troy, Aeneas carries the palladium, a sacred wooden statue to Minerva (2.227-229). Finally, Virgil intertwines the entire Capitoline triad when he depicts Juno complaining to Jupiter about Minerva (1.34-49).

Livy’s description of IOM’s background neglects Minerva explicitly but may implicitly reference the goddess by emphasizing the temple’s manubial origin and relationship to conflict. According to Livy, IOM first emerged from a votum during the Sabine Wars by Rome’s fifth king, Lucius Tarquinius Priscus (r. 616-579 BC) , who later built the temple’s foundation. “He built up with masonry a level space on the Capitol as a site for the temple of Jupiter which he had vowed during the Sabine war, and the magnitude of the work revealed his prophetic anticipation of the future greatness of the place” (1.38). Next, Rome’s seventh King, Lucius Tarquinius Superbus (r. 534-509 BC), designed the temple after initiating the Volscian Wars, “He then sketched out the design of a temple to Jupiter, which in its extent should be worthy of the king of gods and men, worthy of the Roman empire, worthy of the majesty of the City itself” (1.53). Later, conflict again catalyzed the temple’s next construction phase as Tarquin began construction after the war with Gabii. Livy explains, “[Tarquin] turned his attention to the business of the City. The first thing was the temple of Jupiter on the Tarpeian Mount” (1.55). A final conflict, Rome’s civil conflict, preceded IOM’s dedication. After the tyrannical King Tarquin was expelled, Horatius Pulvillus dedicated the temple in 509, the year of Rome’s re-foundation as a republic: “The temple of Jupiter on the Capitol had not yet been dedicated, and the consuls drew lots to decide which should dedicate it. The lot fell to Horatius” (2.8). In each phase of IOM’s development — planning, construction, and dedication — Livy connects the temple to Rome’s conflicts. Thus, it is fitting that IOM celebrates Minerva, the goddess of battle planning and military success.

Both Virgil and Livy play crucial roles in establishing the significance of the Aedes Iuppiter Optimus Maximus Capitolinus in Rome’s identity and religious life. By intricately weaving myth and cultural memory, these authors connect the temple, its deities, and its practices to the legendary figures and events that shaped Rome. The Capitoline Triad, consisting of Jupiter, Juno, and Minerva, represents Rome’s divine heritage and protection, as well as its military prowess and the importance of reverence to these deities. Through the Aeneid and Ad urbe condita, the IOM becomes a cornerstone of Roman identity, culture, and religion, symbolizing the power, unity, and continuity of the Roman state.

Part II: Archaeology and Temple Planning

As a focal point of Roman religious practice and a symbol of Roman power, IOM has long been a subject of scholarly fascination, with archaeologists and historians attempting to unravel the enigma of its design and origins. IOM was not a singularity but instead part of a class of temples informed by particularities of time and place. The archaeological record signals that IOM reflects an early period of temples associated with kings or tyrants and draws from Etruscan influence, or should even be codified as an Etruscan temple.

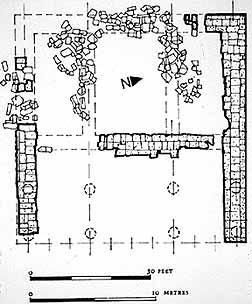

IOM’s extant foundations and Vitruvius’ notes provide a detailed description of IOM that can be measured against other temples from the same period. In De Architectura, Vitruvius delineates the architectural features of the “Tuscan Temple,” such as the three cellae, front stair and porch, and eastward orientation (4.5.1, 4.7.1-5, figure 1). The temple’s extant foundation remains appear consistent with Vitruvius’ model of a Tuscan temple. Specially, the foundations on the south end lack the foundation remains of the north, signaling that the north end featured an interior cellae while the south featured the front porch. While this alignment is not consistent with Vitruvius’ eastward orientation, other elements reinforce Vitruvian ideas. Spaces between extant foundations appear to reflect a dominant center cella, reinforcing Jupiter’s status as “best and greatest” as well as Vitruvius’ rigid Tuscan dimensions of one major center cella and two minor side cellae (figure 2). Comparing these elements to those of other temples from the same period can reveal similarities and differences that suggest Etruscan influence in IOM’s design.

Roughly contemporaneous Etruscan architecture exhibits important similarities to IOM. First, while a bit smaller, Ara Della Regina at Tarquinia, like IOM, has three cellae. However, all three of Ara Della Regina’s cellae appear to be similarly-sized, perhaps diverging from IOM (figure 3). The Portonoccio Temple at Veii exhibits similar traits, including three cellae, a dominant center cella, and a front porch (figure 4).

At Gabii, the Temple of Juno is slightly different, with only one cella, but mirrors other IOM features including a front porch and hexastyle columns (figure 5). Finally, Etruscan tombs at Cerveteri appear to mirror the Tuscan model with three burial chambers, mirroring cellae, and a long descending dromos, mirroring the porch and stairs. These similarities point towards a shared architectural heritage and possibly the influence of Etruscan design principles on the construction of IOM.

History further reinforces IOM’s connection to Etruria. As aforementioned, Livy describes the temple’s construction and dedication by two Etruscan kings (1.38, 1.55, 2.8). Moreover, historical records indicate that an Etruscan architect and artist, Vulca, worked on IOM. Vulca, known for his work on the terracotta sculptures adorning the temple, further strengthens the link between IOM and Etruscan artistic tradition. Indeed, Etruscan-type terracotta has been excavated in the Forum, strengthening the link between IOM and Etruscan style. Finally, the Etruscans had a long history of worship to divine triads. The silver Etruscan mirror from Bomarzo features a divine triad of Apollo, Mercury, and, of course, Jupiter, reinforcing the Etruscan’s relationship to triads and Jupiter “the best and greatest.”

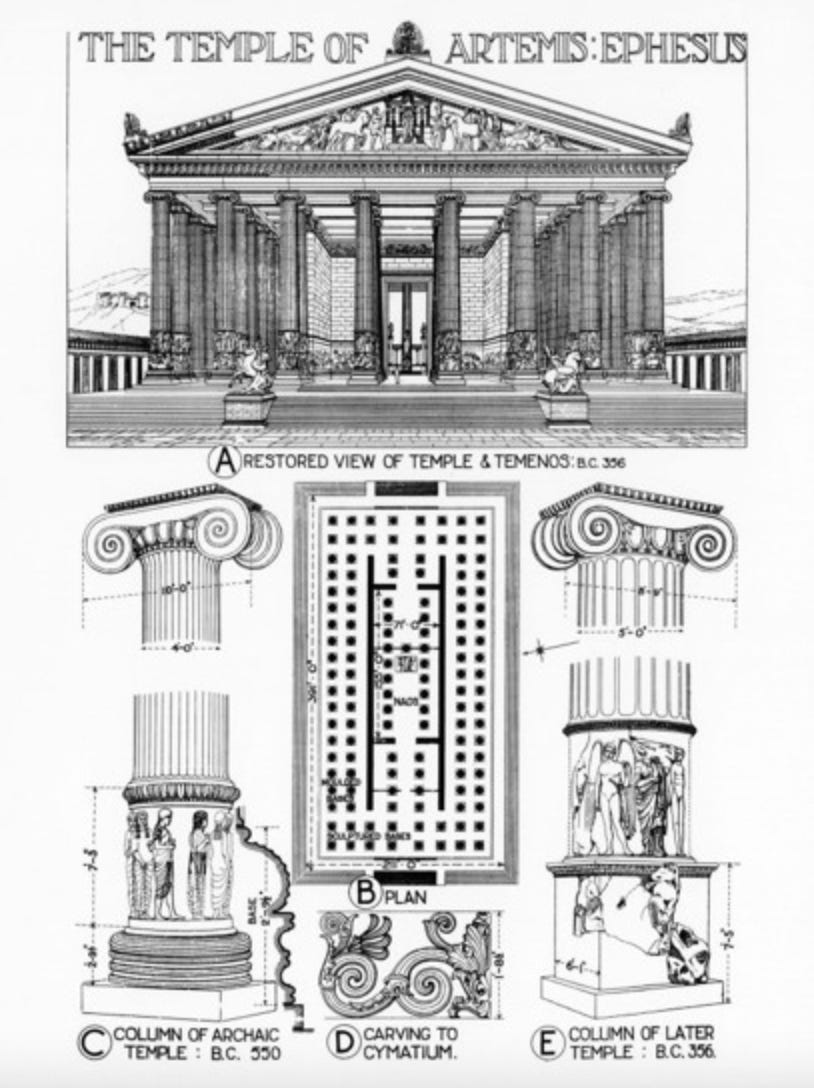

The Greek world provides additional clues about IOM as a class of temple. The Temple of Artemis at Ephesus, one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, shares some striking similarities with IOM. Both temples are contemporaneous and colossal. Additionally, these supertemples were built during periods of kingship, highlighting the association of monumental temples with monarchical political power.

By examining IOM’s design, archaeological remains, and its connections to both Etruscan and Greek architecture, we can uncover the temple's unique position within a broader context of architectural and cultural developments. IOM’s alignment with Etruscan architectural principles, as well as its historical connections to Etruscan kings and artists, strongly suggests that the temple should be understood as part of a larger class of temples influenced by Etruscan tradition, or even as an Etruscan temple in its own right. Furthermore, the comparisons to contemporaneous Greek temples, such as the Temple of Artemis at Ephesus, emphasize the role of grandiose temples in asserting the authority of kings and tyrants. By recognizing IOM’s place within this broader framework, we can better appreciate the intricate interplay between architectural design, religious significance, and political power that shaped this iconic Roman temple.

Bibliography

Bagnasco Gianni, Giovanna, et al. “A Biography of an Ancient Cultural Landscape: The Sky over Tarquinia.” Sustainability, vol. 14, no. 24, 2022, p. 16798., https://doi.org/10.3390/su142416798.

Coarelli. “The Theatre of Pompey.” Gabii, 1993, https://www.pompey.cch.kcl.ac.uk/Italian%20Theatres_files/gabii.htm.

Founded by JAMES LOEB 1911 Edited by JEFFREY HENDERSON. “Ab Urbe Condita.” Loeb Classical Library, https://www.loebclassics.com/view/LCL295/2017/pb_LCL295.xv.xml.

Founded by JAMES LOEB 1911 Edited by JEFFREY HENDERSON. “Aeneid.” Loeb Classical Library, https://www.loebclassics.com/view/virgil-aeneid/1916/pb_LCL063.263.xml.

Founded by JAMES LOEB 1911 Edited by JEFFREY HENDERSON. “De Architectura.” Loeb Classical Library, https://www.loebclassics.com/view/LCL251/1931/volume.xml.

Palmes, J. C. “Temple of Artemis, Ephesus: Plan, Details and Perspective.” RIBApix, Sir Banister Fletcher's A History of Architecture, 1975, https://www.ribapix.com/Temple-of-Artemis-Ephesus-plan-details-and-perspective_RIBA100818.

“Portonaccio Sanctuary Architecture.” Etruscan Art, https://www.ou.edu/class/ahi4163/files/arch2.html.